We’ve been talking for a while to messageboard regular Kushiro, who chronicles the history of Leicester City in fascinating fashion, about a topic for his first contribution to the site.

As a trip to Plymouth approached, all became clear…

One of the joys of researching Leicester City history is the opportunity it gives you to link the story of the football club with the story of the city itself. There’s one example familiar to all of us. Our title triumph was thrilling enough in itself, but the ‘King in the Car Park’ connection elevated it to the level of fairy tale.

This story is in a similar vein, and it’s called ‘The King and The Captain’.

Back for another appearance is Richard III, the King whose bloodied body was carried back to Leicester on the back of a horse. The Captain is Don Revie. His bloodied body was brought back to Leicester in the back of a taxi. Thankfully, he survived. But it was a very close-run thing.

That taxi ride adds a further layer of historical resonance – a journey of 250 miles, tracing the line of the long, straight road the Romans built 2000 years ago. It was called the Fosse Way.

It was the journey back from a game against Plymouth Argyle in 1949, at the climax of a season when, just like 2015/16, the whole country seemed to be supporting Leicester City. In pre-motorway days, the trip took about eight hours, crawling along the A and B roads.

Those of you who make the trip by road on Friday will follow a slightly less direct route, but you’ll get there in half the time. That still makes it the longest trip we’ll do this season, and I’m hoping that, as you set off for Home Park wondering how to fill the time, this story may be of some assistance. It is, as they say, a long read.

Waiting to be discovered

Late in the afternoon on Tuesday, March 1st 1949, Joe Orton left his house on the Saffron Lane estate and set off for an audition. He was 16, and his big chance had arrived. The Leicester Drama Society were staging a production of Shakespeare’s Richard III at the Little Theatre. He was determined to play a part.

The elements that day were providing a suitably dramatic backdrop. A storm the previous night had caused structural damage across the city, and as his bus headed into town, he’d have passed the scene of devastation.

The Old Showground on Saffron Lane was one of four outdoor venues inside a square mile on the south side of the city, the others being Welford Road, the Aylestone Road Cricket Ground and Filbert Street.

That morning, strong winds had ripped the 100-yard long roof off the Showground’s Main Stand, and it now lay, as the Evening Mail described it, ‘pancaked upon a row of wooden huts’. Those huts were, appropriately, in Shakespeare Street. For a young man determined to shake up the cosy world of amateur dramatics, this would have been a delicious piece of symbolism.

Orton got off the bus in the centre of town and headed for the Little Theatre in Dover Street. There he would pass the audition and take the first step towards the fame that, fifty years later, saw his own name join the Bard’s on the street map of Leicester.

Earlier that day at the Little Theatre, before the Richard III audition, pupils from Alderman Newton’s Girls’ School had been rehearsing their production of a play called Everyman. Intriguingly, the scene captured by the Evening Mail photographer featured a skeleton:

When the rehearsal finished, the girls made the short journey back across the city centre to their school in St. Martins. You can see it below. The flat area is the school playground:

Beneath that playground lay another skeleton, waiting to be discovered.

The topic on everybody’s lips in Leicester that day was the FA Cup, and City’s chances of making it to Wembley for the first time ever. The morning papers carried news of the semi-final draw. We’d been paired with the team of the season – Portsmouth. They were five points clear at the top of the League, and they’d have been delighted that, as they chased an historic double, it was the team lying 20th in the Second Division that stood between them and the final. Lowly Leicester – in danger of dropping, not into the second tier as in 2015, but down into the uncharted depths of Division Three South.

At Filbert Street that morning, manager Johnny Duncan was looking on anxiously as his inside forward Don Revie received treatment for a leg injury he’d picked up in the quarter-final on Saturday. He’d played a key part in the 2-0 win at Brentford. Only 21, he was already being spoken of as a candidate for the England tour in the summer.

Even at that young age, photos of Revie show a man who seems to be carrying the weight of the world on his shoulders. After what he’d been through in his short career, perhaps it was understandable.

He’d already had to come through two huge tests of character. One of them was having to face the barracking of his own supporters at Filbert Street. Revie was a player who liked to take time on the ball, something that isn’t always appreciated. This is how he described the crowd’s reactions:

One man saying “get rid!” is only saying what he would do if he were playing in the game. But that cry spreads like an unhealthy rash over the terraces until many thousands of voices are screaming “GET RID OF IT”. The player holding the ball trying to plan an opening is suddenly smitten with doubt and despair about his own capabilities.

It was only with this Cup run that he was finally starting to win people over.

He’d also suffered a horrific injury. Two years earlier, an ankle break was so bad that doctors told him he had a thousand to one chance of playing again. Johnny Duncan’s response was, ‘What say we make you that one man in a thousand, son?’

After nine months out, he made that comeback. He was completely over that ankle break now, and the leg injury being treated that morning at Filbert Street turned out, to Duncan’s relief, to be fairly minor. He’d be fit for the semi-final.

The giant killers

The bookies’ odds to win the Cup on the morning of the semi-finals were as follows:

Portsmouth: 13-8

Manchester United: 7-4

Wolves: 3-1

Leicester City: 10-1

The 69,000 tickets for the game at Highbury had been split three ways – 23,000 for each competing club, and the same number going on sale at Arsenal. Our largest ever away following headed for London, and they witnessed what is arguably our greatest single FA Cup performance. Revie scored twice, Ken Chisholm got the other and we won 3-1. We’d made the final at last. After the game City fans celebrated wildly, with choruses of ‘Poor old Pompey, poor old Pompey!’ chiming long into the London night.

The quality of our performance can be judged from Portsmouth’s reaction to the defeat. The following week they went to Newcastle to face their only remaining rivals in the League. The Geordies knew they had to win to stay in the race, but Pompey came away with an astonishing 5-0 victory. The title race was over.

With a team that good, you can understand how bitterly disappointing the defeat to Leicester would have been (and if you listened to Jon Holmes on the Football Ruined My Life podcast last month talking about his friend Geoffrey Fry, you’ll know that two decades later, the pain was still there).

Our opponents in the final would be Wolves, and once again we’d be huge underdogs. Neutrals would be on our side. Never before (and never since) had a team so low in the League reached the final. As the Evening Mail put it: In the game’s long history there has been nothing more romantic than the City’s astounding rise from the shadows in the first half of the season to their present eminence.

But Johnny Duncan wasn’t getting carried away. Before the final, he had to get the players focused on the battle to avoid relegation. Our main rivals at the bottom were Nottingham Forest – and when we lost 2-1 at the City Ground on April 9th, it looked like we might achieve a truly unique double: Cup glory and relegation to the third tier.

The King and The Captain take the stage

Joe Orton was given two small parts in the play – ‘the messenger’ and ‘a soldier’. He would have very few lines, but he didn’t care. He was on the first rung of the ladder. The part of Richard III would be played by an actor called David Lyall, and the play would run from April 18th to April 27th:

It’s at this point that two timelines overlap perfectly, because the real-life drama that Revie was about to go through would unfold over exactly the same ten-day period.

Easter Monday, April 18th

There were two big events in town that day. Leicester’s game against West Ham kicked off at 3.15, while the opening night of Richard III was scheduled to begin at 7pm.

This was the bottom of Division Two before the game:

Set designers making last minute preparations at the Little Theatre would have been impressed by the scene at Filbert Street as another piece of drama, choreographed by Johnny Duncan, played out against a stunning backdrop. Duncan had decided that the young man was ready, and when the team ran out, the crowd caught on. Leicester City had a new captain, and his name was Don Revie.

That backdrop? These photos give you an idea of how Filbert Street looked at that time. They were taken a few weeks earlier during our Fifth Round Replay against Luton.

You can see the south wing of the Main Stand, gutted in a wartime fire and yet to be repaired. Further along the Main Stand, below, as Luton celebrate a goal you can see what Simon Inglis called ‘one of the grandest stage entrances any player could wish for’:

Zooming in below we can see it more clearly, ‘a mock classical podium, with pilasters, a small window on either side and brass rails above, lining the front of the directors’ box’ (Inglis’ words again). The man with hands on hips is Don Revie:

In the early 1950s that entrance was crudely blocked in when terracing was extended on either side (those photos from the excellent Hatters Heritage site).

Just a few minutes into the game against West Ham, there was a clash of heads between Revie and their centre half Dick Walker. Revie was left with blood streaming from his nose, but after receiving treatment, he carried on. It didn’t seem like a serious injury.

We got a crucial point in a 1-1 draw, but when the players came off the pitch they learned that Forest had won 2-1 at Bradford Park Avenue to move ahead of us on goal average.

It wasn’t just the timelines that were overlapping. The 400 people with tickets to see Richard III and the 30,000 heading home after the final whistle would not have been entirely separate populations. Some of the Leicester fans would have headed straight for the Little Theatre, mixing with the West Ham fans on the way back to the station in the familiar post-match throng on Aylestone Road, blocking the traffic. Joe Orton, heading for his stage debut, may well have been one of those people on the top deck of a bus, looking down on the scene with a mixture of bemusement and frustration.

In the Evening Mail the next day, the report of the match sat alongside a review of the play. This, meanwhile, was the Mercury’s front page:

The picture shows Post Office employees at Filbert Street with sacks of Wembley ticket applications. Our allocation was 12,000, and after the 4,000 season ticket holders were accounted for, there were very few to go around. In the next few days, more sacks of mail arrived and in the end, each application had only a one in 13 chance of being successful.

On April 21st, night four for the Richard III cast, Revie played in our next fixture, a 3-1 win over Blackburn Rovers at Filbert Street that saw us leapfrog back over Forest and give us some crucial breathing space. The nose bleeds had not fully stopped, but Revie still didn’t consider it a serious problem, and nor did his manager.

The next morning, Friday 22nd, the squad made the long train journey to Plymouth where they booked in to the famous Grand Hotel, overlooking the Hoe, where Revie would share a room with Ken Chisholm:

The Grand is circled on the left (and we’ll come to that other circle soon).

Home Park is two miles inland. It was another ground to suffer wartime damage. The Main Stand was completely destroyed, leaving no covered seating at all for Argyle fans:

That stand had been on the left, replaced here by temporary bench seats (photo from another great history site, greensonscreen.co.uk).

Revie had picked up a slight groin strain in the Blackburn game, and Duncan decided to rest him against Plymouth. He wanted him fit for the final, just seven days away. Without him we looked not like Cup finalists, but ‘just another struggling Second Division outfit’. Still, we came away with a 1-1 draw, while Forest drew 2-2 with Spurs at the City Ground.

It was that evening that Revie’s condition suddenly worsened.

Bloody Thou Art, Bloody Will Be Thy End

Around the time Queen Elizabeth was saying those famous words to Richard III on night six at the Little Theatre, this is what happened at the Grand Hotel:

As Ken Chisholm came into the room, he saw me hunched over the washbowl, my nose streaming with blood. He clattered down the stairs and shouted for the trainer, Willie McLean, to come up to me.

I had been huddled over that bowl for ninety minutes. At first it was only a trickle, and I thought it wasn’t worth bothering anybody. Then I thought it was the bruising coming out and I could stop it with cold water.

Willie McLean and his assistant George Ritchie dashed into the room and hastily draped two pillows over my head. For two hours they applied ice-packs made up in the hotel refrigerator and gradually the bleeding stopped.

On Sunday morning, as he got out of bed, the bleeding started again, and this time he was rushed to hospital in an ambulance. The hospital, the South Devon and East Cornwall, is the other building circled in the photo above, fortunately just around the corner. You wouldn’t want to be making long journeys in that condition.

That morning, the City squad headed for home while Revie stayed in hospital. Doctors told him a vessel at the back of his nose had been punctured. He was kept in overnight, and on Monday the doctors told him they wanted him to stay longer.

Johnny Duncan had other ideas. Wembley was only five days away, and he told Revie ‘I think your recovery will be quicker if you are back in Leicester’. He had contacted the Royal Infirmary and arranged for Dr. Nicholas Kendall, head of the Ear, Nose and Throat department, to see him on Wednesday 27th. That meant a journey back on Tuesday.

He took his young star out of the Plymouth hospital late on Monday, but they couldn’t go back to the Grand Hotel, which was fully booked. Bob Heath, the hotel’s owner and also a Plymouth director, offered Revie a bed for the night at his house.

Duncan had originally planned to take Revie back on the train the next morning, but for reasons that are unclear, the plans changed, and he decided to book a taxi. They’d be following the route of The Fosse Way.

At 10 am on Tuesday morning they set off on the journey past Ilchester, Bath, Cirencester, and Stretton-under-Fosse. Revie was completely oblivious to these ancient place names, ‘huddled in the back seat, with a load of ice packs’.

‘All the way, Johnny kept up his cheery chatter, giving me sips of brandy. I needed it, for my nose would not stop bleeding, and we were on the road for eight hours.

I was as weak as a kitten as we rolled into Leicester. The specialists were waiting as I was carried into hospital. I hardly knew what was happening, but such is the fever of Wembley that I managed to stammer weakly, ‘Can you stop the bleeding in time for me to play in the Final?’ Then I must have fainted.

The doctors broke the news to me later. ‘Play? You’ve lost so much blood on the way here that if you had been on the road for another hour you might have died’.

Duncan finally had to see sense. He’d planned to take Revie to Skegness on Wednesday to join up with the rest of the squad (passing through Lincoln and thus completing a trip, spread over two days, along the full length of the Fosse Way). But that was now impossible.

Revie had a blood transfusion on that day, April 27th, and Joe Orton passed by again on the bus on the way to the last night of the play. Revie was told he wouldn’t be allowed to travel to Wembley even to watch the game. He was staying in hospital and he’d have to listen on the wireless.

What happened next

We lost the final, of course, but it was so close:

I’ve tried doing a bit of VAR on the footage of our disallowed equaliser, freezing it at the moment Mal Griffiths flicks the ball through to Chisholm (at the top of the picture). The angle’s far from perfect, but it looks like the left heel of the Wolves defender is level with Chisholm’s left shoulder.

Just a fraction of a second later the alignment was different, triggering the flag.

Had we pulled it back to 2-2 and gone to a replay we’d have been jumping for joy, but it would have presented a huge scheduling problem. We still had three League games to play, and the Football League insisted that everything be decided by May 7th, the following Saturday.

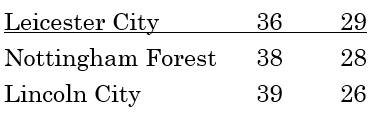

On Cup Final Day, Forest were in London too. They got a sensational 5-0 win at Upton Park which left the table looking like this:

With Forest’s goal average being much better, we knew we needed three points from three games (two points for a win in those days) to be sure of staying up. Those games were scheduled like this:

-

Wednesday: Bury (A)

-

Thursday: West Brom (H)

-

Saturday: Cardiff (A)

We won at Bury, lost at home to West Brom, then Chisholm’s equaliser at Ninian Park gave us the point that kept us up – a goal celebrated even by Cardiff fans.

If the Cup Final had been drawn, the replay would have been on Wednesday at Villa Park, with the Bury game switched to the Friday. It would have meant an unbelievable sequence of four games in four days:

-

Wednesday: FA Cup Final Replay

-

Thursday: West Brom (H)

-

Friday: Bury (A)

-

Saturday: Cardiff (A)

At the start of the following season, Leicester City supporters were let in on the secret.

Don Revie was about to join Johnny Duncan’s family. He had fallen in love with Duncan’s niece, Elsie, on a trip to Scotland when he was just 17, and she had moved down to Leicester in 1948. Elsie was the daughter of Tommy Duncan, who played for Leicester City alongside brother Johnny in the 1920s. He had passed away in 1940.

That relationship, though, signalled the end of Revie’s days as a Leicester player. He didn’t want to be seen as the manager’s pet. He knew what had happened to Jimmy Harrison, his teammate. Harrison had recently married Doreen, the daughter of chairman Len Shipman, and been barracked by the Filbert Street crowd. Revie had experienced enough abuse already.

He signed for Hull City that autumn, though ironically, Duncan quit the club before the wedding took place, and spent the rest of his days running his pub, The Turk’s Head, opposite Leicester prison.

What a shame Revie couldn’t have stayed longer. He later experienced great success as a player at Manchester City, finally getting the chance to play in an FA Cup Final, winning the Footballer of the Year award, and becoming an England regular. But reflecting on his career, he would write that, of the five clubs he played for, Leicester City was ‘the only one where I truly felt part of the club’.

Want more?

For those of you who really did start reading as you set off for Plymouth, I’m sorry if that filled up just a small part of your journey. I imagine you’re still this side of Watling Street.

But if you enjoyed this article, there’s a lot more in the same vein over at Foxestalk.

document.getElementById(‘newsnowlogo’).onclick=function(){ window.open(‘https://www.newsnow.co.uk/h/Sport/Football/Premier+League/Leicester+City’,’newsnow’); }; document.getElementById(‘newsnowlogo’).style.cursor=’pointer’; document.getElementById(‘newsnowlogo_a’).style.textDecoration=’none’; document.getElementById(‘newsnowlogo_a’).style.borderBottom=’0 none’;